What is an ice shelf?

Melting Ice Shelves

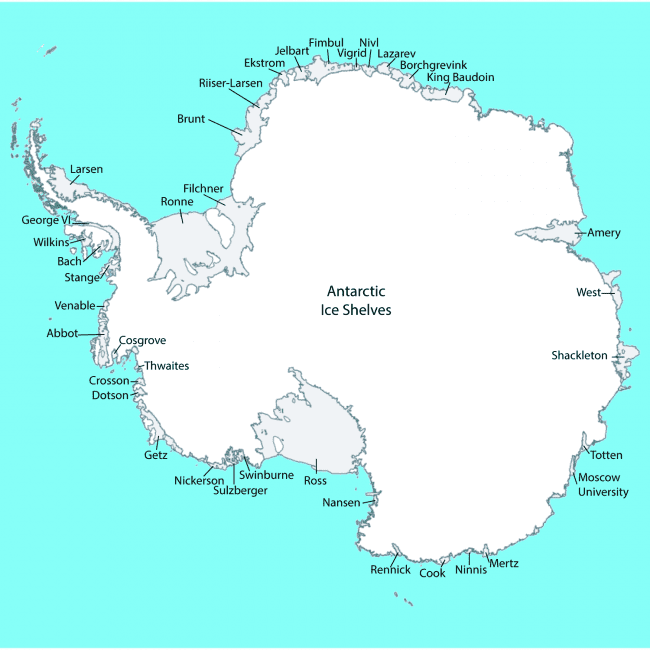

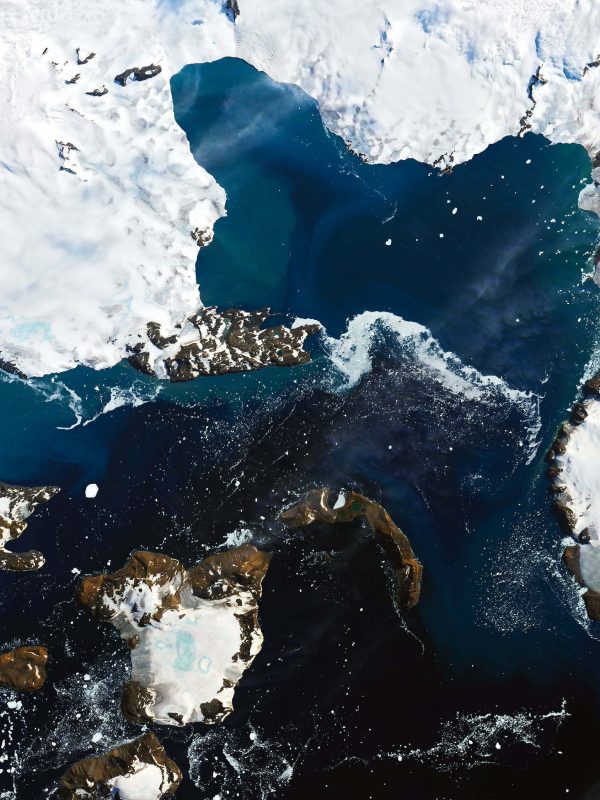

Ice shelves are floating glaciers – the outer edges of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. There are approximately 300 ice shelves around Antarctica. Together they cover around three quarters of the Antarctic coastline – roughly the same area as the entire Greenland Ice Sheet.

The larger Antarctic ice shelves are the size of small nations and over a hundred feet thick. The largest ice shelf on earth, the Ross Ice Shelf, is almost as large as France. It terminates in an ice cliff more than 370 miles (600 kilometers) long, towering up to 160 feet (150 meters) above the ocean.

ICE SHELVES

Antarctica’s ice shelves are shrinking

Every year for the past 25 years, Antarctic ice shelves have been losing mass. Many of them are becoming thinner, smaller and more vulnerable to sudden collapse on a large scale.

MELTING ICE SHELVES

What’s driving the changes?

Warm ocean currents

Warm ocean currents are the main driver behind accelerated melting of ice shelves around Antarctica.

Read more

Warm ocean currents

Warm ocean currents are the main driver behind accelerated melting of ice shelves around Antarctica.

Around the Antarctic coastline, warm, deep-water currents are flowing beneath ice shelves, melting them from below. This makes ice shelves thinner and weaker, and more vulnerable to breaking apart.

Stronger winds

Strong winds around Antarctica are driving warmer currents to the edge of the continent.

Read more

Stronger winds

Strong winds around Antarctica are driving warmer currents to the edge of the continent.

Evidence shows that the climate crisis is changing wind patterns around Antarctica. Winds around Antarctica have strengthened in recent decades due to ozone depletion and changing temperatures in the tropics and the polar regions, which are caused by human activity such as burning fossil fuels. Stronger winds are pushing warm currents towards the Antarctic coast more frequently and intensely.

While the influence of ozone depletion will decrease as the ozone hole recovers in the coming decades, the other drivers will likely persist, particularly if we continue with business as usual carbon emissions.

Warmer air

On the Antarctic Peninsula, the ice is melting not only from below but also above.

Read more

Warmer air

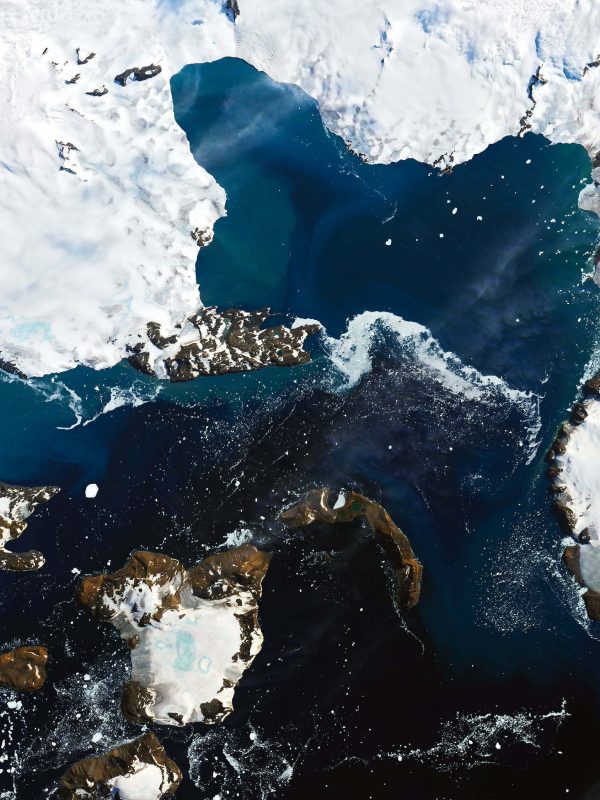

On the Antarctic Peninsula, the ice is melting not only from below but also above.

In this northern part of Antarctica, summer temperatures are rising, and warm air and summer winds are causing widespread melting at the surface.

Warmer air temperatures are causing the surface of some ice shelves to melt during the summer. Meltwater can flow into small cracks in the surface of the ice, leading to a build-up of pressure which can create fractures in the ice. Ultimately, surface melt makes ice shelves weaker, and more likely to break apart.

Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory image showing melting on the ice cap of Eagle Island by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey

How do ice shelves affect rising sea levels?

MELTING ICE SHELVES

Collapsing ice shelves don’t contribute directly to rising sea levels because they are already floating on the ocean, but they do offer a critical line of defense. Ice shelves act as a brake for the glaciers that make up the Antarctic Ice Sheet. When ice shelves melt the glaciers behind them soon follow, contributing directly to sea level rise.

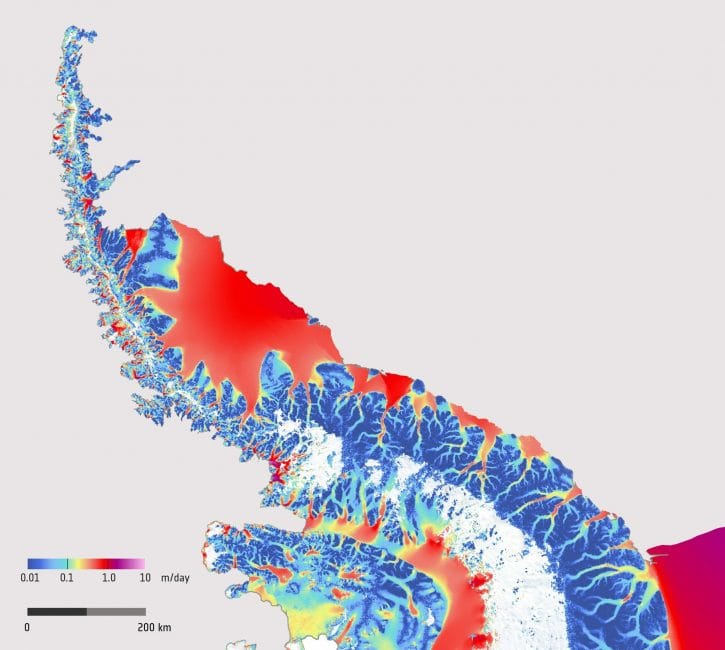

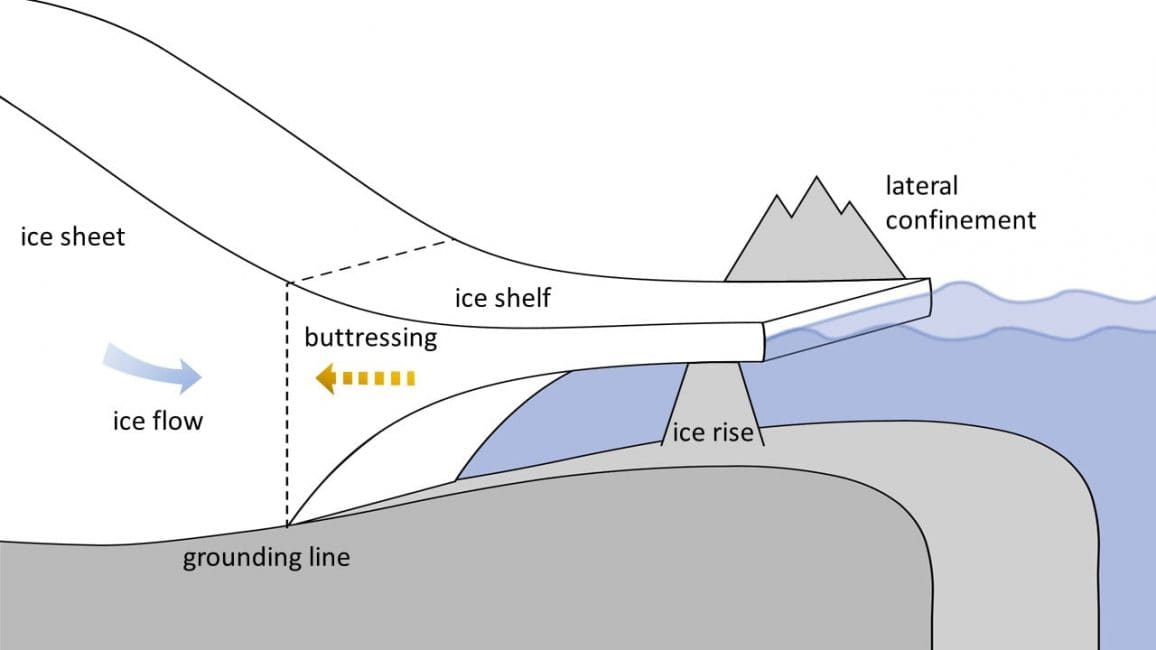

Ice shelves slow the flow of the ice sheet by pushing back against the glaciers that feed them, helping to slow their flow by acting as a buttress, or a braking system for the ice. As ice shelves flow out over bays and inlets they may run into obstacles, such as peninsulas, islands or ice rises. These ’pinning points’ obstruct the flow of the ice shelf and slow it down.

As the ice shelf continues to push against these features, pressure builds up. This pressure is transferred back against the ice sheet, restricting its flow. When ice shelves break apart, this backward pressure is released and glaciers can flow unrestrained into the sea.

Case Study 1

MELTING ICE SHELVES

The collapse of Larsen B

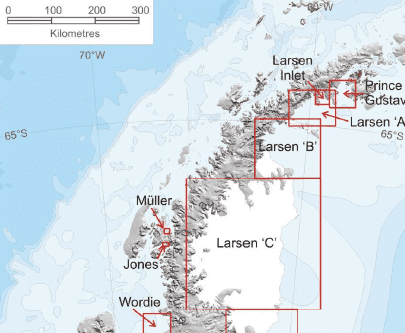

The Larsen Ice Shelf extends along the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula and flows east over the Weddell Sea. It is the northernmost ice shelf in Antarctica, and includes seven distinct sectors named A to G. Larsen A collapsed in 1995, having been in place for 4,000 years.

When the Larsen B sector collapsed in February 2002 it was the largest and most rapid event of its kind scientists had ever seen. In one month, a part of the Larsen B sector covering 1,250 square miles (3,250 sq km) – an area roughly the same size as Yosemite National Park – broke away from the shelf. The ice shelf had been in place since the last glacial period 10,000 years ago.

Glaciers flowing faster

MELTING ICE SHELVES

After this partial collapse, scientists reported that sections of the glacier flowing down behind the collapsed part of the shelf sped up as much as eightfold – the equivalent of a car accelerating from 55 to 440 mph. The ice shelf had been serving as a ‘brake’ on the flow of the ice behind it, and without it the glacier was free to flow into the sea.

The Antarctic Peninsula is warming faster than any other part of Antarctica. In fact, it is one of the fastest-warming places in the Southern Hemisphere. The extensive Larsen B calving event is thought to have been accelerated by warm summer temperatures and warm ocean currents melting the ice from below.

WATCH THIS SHORT VIDEO

The collapse of the Larsen B Ice Shelf

Prior to collapse, the Larsen B Ice Shelf covered 1,250 square miles (3,250 square kilometers) and was around 220m thick (720 feet).

Case Study 2

MELTING ICE SHELVES

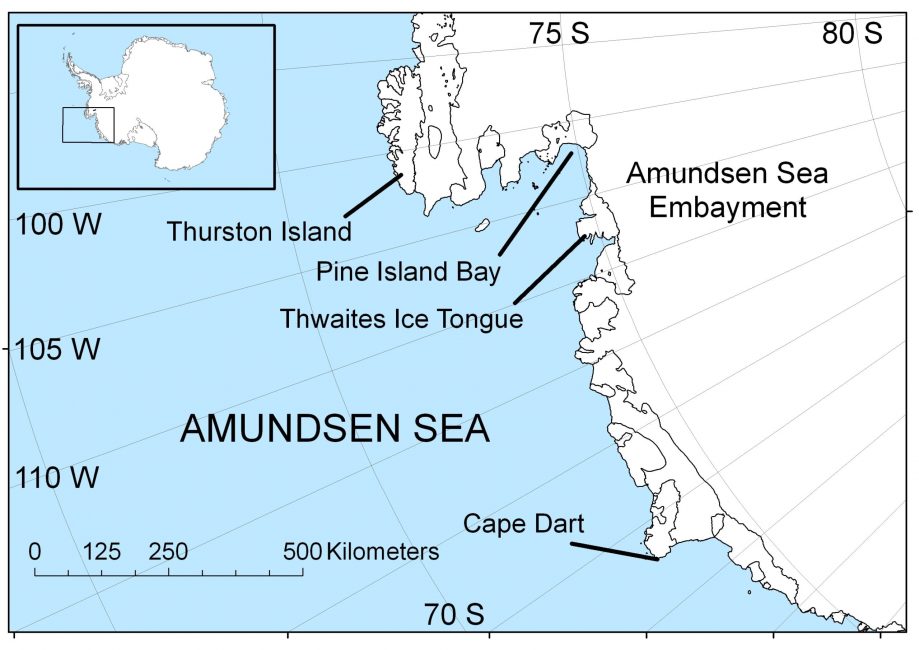

Thwaites Glacier, West Antarctica

At around 980 feet (300 meters) thick, the Thwaites Ice Shelf is one of the biggest ice shelves in West Antarctica: roughly the size of Florida. In the 1990s Thwaites was losing just over 10 billion tons of ice a year. By 2020 it was more like 80 billion tons, an eightfold increase in less than 30 years. Most of this has been attributed to warm ocean currents melting the ice from underneath.

The Thwaites Glacier has been described by some researchers as a ‘cork in a bottle’. It lies at the heart of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, a region particularly vulnerable to rapid melting due to the shape of the land under the ice. The instability of the ice in this region means that if ice in the region continues to melt rapidly, it could reach irreversible tipping points without warning.

KEEP LEARNING

Related reading

Scientific consultation: Tas Van Ommen, Antarctic climate scientist specializing in ice core palaeoclimate and glaciology.

Now that you’ve learned about how Antarctic ice shelves are changing, read on to learn more about this extraordinary continent.

ASOC

ASOC